If you’re looking for a way to turn a novel into short stories or (more likely) turn stories into a novel, try these activities.

Novels into Stories

1.) Read “The Beau Monde of Mrs. Bridge,” a short story by Evan S. Connell published in The Paris Review 10, Fall 1955.

2.) Take a good look at this short story. If you’ve read the book, then you know that Mrs. Bridge the novel is comprised of 117 titled vignettes. But “Mrs Bridge” the short story pre-dates the novel. “Beau Monde” the short story contains 12 of the eventual novel’s vignettes (in this order: 61, 39, 37, 60, 91, 99, 84, 86, 18, 102, 41, plus one titled “Equality” not found in the novel).

vignettes (in this order: 61, 39, 37, 60, 91, 99, 84, 86, 18, 102, 41, plus one titled “Equality” not found in the novel).

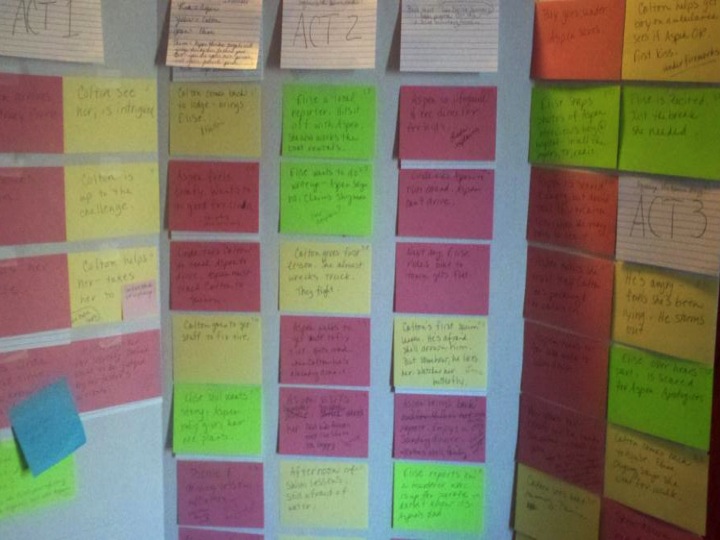

3.) Pretend for a moment that you are Evan S. Connell. You wrote the short story “Beau Monde” because you wanted to satirize the small-minded racial and class politics of your hometown. And you did that. Quite successfully. It’s just out in this new magazine called The Paris Review. But now what? Maybe you’re not quite done with this Mrs. Bridge. What about her husband? How did they meet? What would happen if this very American couple went on a European tour? What of her children? How will she respond when they grow up and challenge her worldview? And what about her best friend, Grace Barron? You open up the pleats. You write more vignettes. Most fit on a single piece of typing paper. They’re more than scenes, but less than chapters. They’re what Mark Oppenheimer in The Believer calls “chapterlets.” In fifty years or so, people might call them “flash fictions.” Each vignette is a building block, a movable unit, a piece of paper. You lay them out on the floor, tape them to the walls, trying to figure out how they go together.

This is exactly what I wanted to do when I finished the book: tear out the pages and lay them on the floor, tape them to the walls. I wanted them to be tangible, detachable things. So, I used post-it notes to create a thumbnail sketch of each vignette. This really didn’t take that long because I’d just read the book. A few hours. Continue reading