Teaching Tuesday: Learn their Names

On the first day of any class I teach, I learn all their names.

First, I call roll. I request that they tell me:

- what they prefer to be called

- the name and location of their hometown

I learned a lot about the states of Alabama, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania this way, and now that I’m teaching back home again in Indiana, I’m familiar with most of the towns they name.

Every once in awhile, I’ll get a student from Peru, Indiana, my hometown. Last semester, I had a young woman from Peru who was the cousin of a boy I “went with” in the 8th grade (although I didn’t tell her that).

I try to have a brief conversation with each student about where they’re from, where it’s located, what it’s famous for. Something. Anything. I make a connection. This can take awhile.

Then I go down the roll sheet again and try to identify everyone—and remember their hometowns.

Then I put the roll sheet down and go around the room, point to each student, and try to recall their first name. I keep going until I get them all right.

I tell them this. “I might see you in an airport five years from now, and I’ll remember your face and where you sat in my class, but I will not remember your name. At the end of this semester, I do a brain dump.” But for now, I want to know who they are.

Then, and only then, we go over the syllabus, etc.

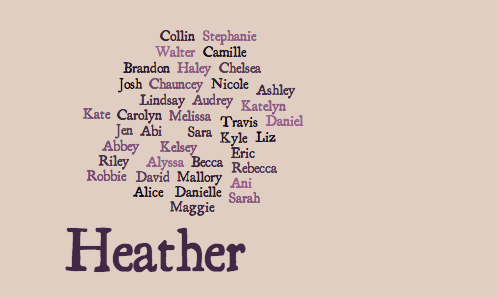

How many names are we talking about here? When I taught undergraduate general education classes, I often had 35 students per class. Now I teach mostly majors, and I tend to have 15 or 20 students per class, three classes per semester. So: at maximum, we’re talking 60 names. Usually less. This semester, it’s 40.

At The College of New Jersey, I once had a class with seven Matts. I kid you not.

I’ve noticed that many of my students seem startled that I’m making this effort to learn their names. I’m not sure why this is.

I learn their names because I think it sets a good tone for the semester. I want them to know that I care about who they are as individuals. Sometimes students will work harder if they feel like you might be disappointed in them if they slack off. I want my class to be at the top of their priority list.

I do this because I think that students very quickly make up their minds about whether or not they like a class and their teacher. I know I did when I was in college, and this study bears that out. That first day, they’re taking stock of their semester, what’s on their plate, with whom they’re going to be dealing. I want my class to be their favorite, if at all possible–although if it’s not, that’s okay. (It’s taken me a long time to accept that, actually.)

I do this because being a good teacher isn’t just about your syllabus, how smart you are, how knowledgeable, how you’re perceived in your discipline. It’s about whether or not you have the ability to get through to people. Sometimes, I’m capable of this. Not all the time (and I’d be happy to show you my evals, which are sometimes mixed), only sometimes.

I try for “most of the time.” And spending most of the first class learning all their names is a good start.

Teaching

I admire your effort, Cathy. I think what your students are alarmed by is that you are learning their names so fast, memorizing them right in front of them. They fear for you! Such a feat! I try to learn all mine’s names by the second or third class, and they think nothing of it; of course, it’s not as impressive as what you do.

I use the hometown thing too but don’t draw it out as much, like your great idea of having them tell a notable thing. But there seems to be a problem with this “where are your from” approach at my school I can’t seem to get around. Virtually all our kids are from Ohio, and most are from our greater metropolitan area—and a lot of kids seem actively or vaguely embarrassed by this. It would be like if you taught in Indy and all your students were from there or from a few miles away. All the same, something about a location helps me, too. Maybe if I asked them their hometown and one thing it’s famous for that would take the curse off?

This year I tried having them name their favorite book and movie, which may mildly help as an ice-breaker but otherwise did not help ME. So I ALSO asked them hometowns. All that was too much and did not help me learn their names better and, as I said, was kind of a dud as an icebreaker, if that’s what it was supposed to be—someone suggested it to me.

In my real life, I’m pretty terrible with names. You can introduce yourself to me and I’ll forget your name immediately. At family gatherings I have to have one of my younger brothers stand beside me, murmuring, That’s cousin David and that’s son, Joshua. But in the classroom, I am a genius at names. In the Novel in Month class we’ve gotten as many as 55 people. I can go around the room after only a few minutes and name them all without a miss. They can change seats, clothing, and I’ll still remember them the next week, and for the rest of the term. But, like you, once it’s over, I’ll have no idea who they are. The names flee after class ends. I have no idea how I manage this.

Interestingly, the students at Extension are always excited by my little name trick. After I named the 55 people, someone said, You should go on Oprah. The zenith of achievement, apparently. The undergraduate class I taught was not so impressed. The people who dropped after the first night said the class was not “warm and welcoming.” I thought I was running a workshop, not serving a home-cooked meal. One learns.