My last blog post went up four years ago. Wow.

Remember when I was blogging all the time? Boy, I really had a lot to say.

Then I got caught up in administrative work and lost the digital sharing spark. I suppose I didn’t have enough fire left at the end of the day to share with you. And most days, I couldn’t talk about what I was working on.

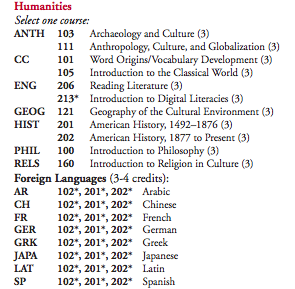

The last four years of my professional life:

After serving as a Director of Undergraduate Studies in English for three years, I then served as an interim department chair for 18 months. During that period, I put together a proposal for my dean. “Here are the things that worked in my department re: recruitment, retention, and placement. Let me build this out for the humanities departments.” Amazingly, the dean said okay. This is what I’ve been working on.

Which brings us to Monday, Jan. 10, 2022, which will be my first day back in an actual classroom since March 9, 2020. I’m incredibly nervous about teaching face-to-face, but that’s not what I want to talk right now.

The Class “Career Talk”

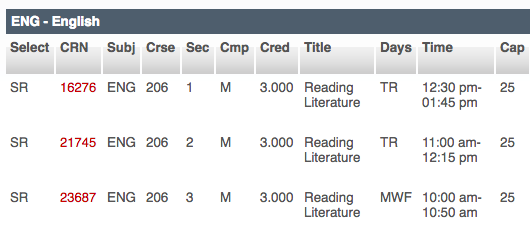

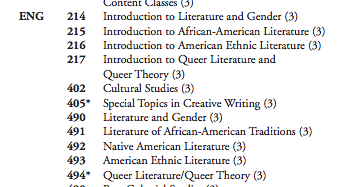

The class I’m teaching in Spring 2022 is ENG 405 Special Topics in Creative Writing. My topic is “Writers at Work: The Business of Being a Writer.”

As the Director of Compass, I’m also in charge of career programming (and yes, I have a course release for this purpose), and so I inserted a weekly career series into my class. Basically, I’m turning the lecture/discussion portion of the class into a public virtual event.

This is the schedule for the first 8 weeks. Then, during the second eight weeks, the topics will turn more generally towards how to find a job.

I’m not telling you about this so that you can come, too. Sorry, but it’s for Ball State students, faculty, and staff only.

I’m showing you what I’m doing so that you can do it, too.

Almost every English department faculty member I know incorporates at least one unit of “career talk” into certain classes. How to submit your work for publication. How to (or whether) to apply to graduate school. How to make time for writing. Maybe you bring someone from the Career Center in to talk about resumes or interviews.

Yay! Good for you.

The problem with this approach:

- Only students who happen to be in your class are exposed to these really important and much-desired “beyond craft” or “off-the-course-topic” conversations.

- These conversations could go a looooooooooooong way toward alleviating the anxiety of humanities majors who are feeling the normal amount of “what am I going to do with my life?” stress times Covid times 1000.

- These “professionalization-unit-within-the-class” conversations are completely invisible to prospective students checking out your website or the unhappy accounting major who loves to read who follows your department on social media.

- Your colleagues down the hall don’t know about your professionalization unit within your class. They might be doing the exact same work as you. Or they might have students who desperately want the very information you just shared, but they don’t know you’ve got resources at the ready.

Making Your “Career Talk” More Visible and Accessible

Survey faculty in your area to find out how many incorporate professionalization units into their classes and what they’d feel comfortable presenting on.

Incorporate into your existing visiting writers series, just one or three or four more casual events. No one is flying in and you’re not paying anyone, so these events are candy compared to putting on readings or lectures. If that doesn’t work…

Create a series. Keep it simple, but aim for something more structured than an off-the-cuff chat. If one colleague has a powerpoint presentation, great. Another just has a handout? That’s fine.

Create takeaways. Make it your goal that for each event/presentation, attendees will get a “takeaway” handout with powerpoint slides and/or links to further resources. Put it all in a Google Drive or Box or OneDrive or Dropbox folder and share the link to that information during the presentation.

Incorporate the series into a class. If you can. That’s what I’m doing, and it means there will always be an audience–the students in the class!

If you can’t make it curricular, make it co-curricular. But you don’t have to do it alone.

Talk to potential co-sponsors to help with organization and promotion: a department administrator, a student organization, the career center, alumni affairs (esp. if the professionalization unit involves Zooming with an alum).

- At Ball State, I’ve discovered that there are good resources in the “living/learning community” arm of residence life. There’s a new dorm for Humanities students with a really nice multipurpose room. There’s an Academic Peer Mentor–sort of like an RA, but just for academics–who is always looking for programming ideas. We’ve worked with them to co-sponsor a humanities activity fair in September and NaNoWriMo events in November.

Promote the hell out of it. Not just because you want a lot of students to come, but also because:

- it’s good for morale (people like to know that there’s an active community they can plug into when they are ready).

- it’s good for recruitment (obviously).

- it’s good for alumni relations (an alum sees what you’re doing and gets in touch to say, Hey, I’d be happy to talk about X.)

But here’s the rub…

Promoting the hell out it means that you have to do more than send emails. People outside the department can’t read your emails. They also can’t see that cool poster you made and printed and hung in the hallways.

Does your school have a website calendar? Get these events on there.

Does your department have a blog or social media? Get on that.

Does your department have an alumni newsletter? Make sure that you mention that these events are going to happen or that they did happen in your newsletter.

Send an email to the student newspaper and see if they’ll promote or cover the event.

This is where your eyes glaze over. Because who has time to do all that? It’s just soooooooo much easier to talk about the topic in your class on a particular day and be done with it.

I don’t know if there’s anybody in your department who is in charge of making shit happen. Besides the chair. I don’t know if that person is resourced adequately. Probably not.

In the real world, community building and coordination and planning and promoting and getting shit on the internet is JOB ONE. Even at colleges and universities. But at the academic unit level–it’s the stuff no one wants to do. The invisible work. The stuff we delegate. Women’s work. Give it to the secretary, the intern, the GA. If you still have anyone to delegate to, if financial exigencies haven’t taken those resources away.

People outside the academy just don’t understand how difficult it is to make something new happen.

Look. Talk to your colleagues. Show them this schedule and ask, “Hey, can’t we put something like this together?” I’ll bet you can.

Then get the word out as best you can. Whatever you do, I promise it will make a difference.

I go the restroom to wash my face before bed and pump some soap out of the dispensers. And the girls hold out these light green tubes and ask me why don’t I use Clinique, and I ask, “What’s Clinique?”

I go the restroom to wash my face before bed and pump some soap out of the dispensers. And the girls hold out these light green tubes and ask me why don’t I use Clinique, and I ask, “What’s Clinique?”

The book

The book

Know this: every department believes that all college students should be required to take one of their classes.

Know this: every department believes that all college students should be required to take one of their classes.