How to turn stories into a novel, or vice versa

If you’re looking for a way to turn a novel into short stories or (more likely) turn stories into a novel, try these activities.

Novels into Stories

1.) Read “The Beau Monde of Mrs. Bridge,” a short story by Evan S. Connell published in The Paris Review 10, Fall 1955.

2.) Take a good look at this short story. If you’ve read the book, then you know that Mrs. Bridge the novel is comprised of 117 titled vignettes. But “Mrs Bridge” the short story pre-dates the novel. “Beau Monde” the short story contains 12 of the eventual novel’s vignettes (in this order: 61, 39, 37, 60, 91, 99, 84, 86, 18, 102, 41, plus one titled “Equality” not found in the novel).

vignettes (in this order: 61, 39, 37, 60, 91, 99, 84, 86, 18, 102, 41, plus one titled “Equality” not found in the novel).

3.) Pretend for a moment that you are Evan S. Connell. You wrote the short story “Beau Monde” because you wanted to satirize the small-minded racial and class politics of your hometown. And you did that. Quite successfully. It’s just out in this new magazine called The Paris Review. But now what? Maybe you’re not quite done with this Mrs. Bridge. What about her husband? How did they meet? What would happen if this very American couple went on a European tour? What of her children? How will she respond when they grow up and challenge her worldview? And what about her best friend, Grace Barron? You open up the pleats. You write more vignettes. Most fit on a single piece of typing paper. They’re more than scenes, but less than chapters. They’re what Mark Oppenheimer in The Believer calls “chapterlets.” In fifty years or so, people might call them “flash fictions.” Each vignette is a building block, a movable unit, a piece of paper. You lay them out on the floor, tape them to the walls, trying to figure out how they go together.

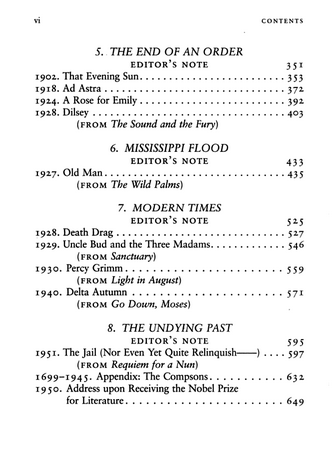

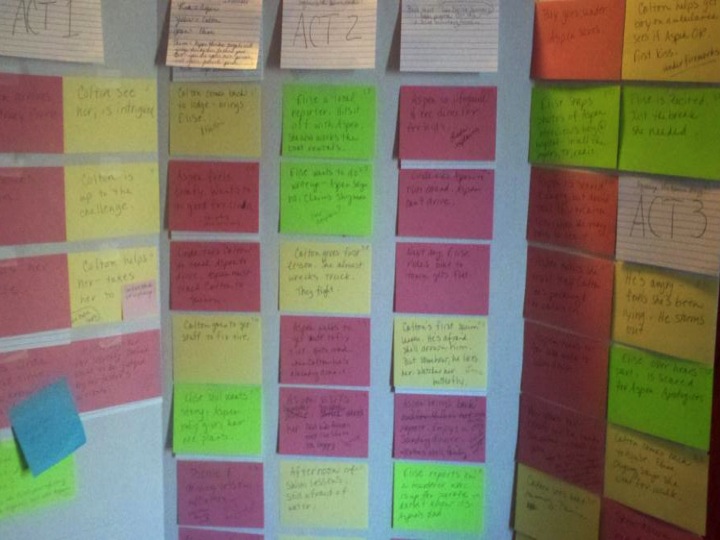

This is exactly what I wanted to do when I finished the book: tear out the pages and lay them on the floor, tape them to the walls. I wanted them to be tangible, detachable things. So, I used post-it notes to create a thumbnail sketch of each vignette. This really didn’t take that long because I’d just read the book. A few hours.

4.) Now you do it. Using index cards or post its, summarize each vignette. Use different colors to trace different “through lines” and subplots.

You can do it by character:

- Ruth in red.

- Douglas in green.

- Carolyn in yellow.

- Mr. Bridge in blue.

- Grace Barron in purple.

- etc.

Or do it by subject matter:

- Self-improvement.

- Americans in Paris.

- The Car.

- The Help

- When the Children Start Dating

5.) Move the cards around. That’s the point. Lay out a line of red cards, followed by a line of yellow cards, followed by a line of blue, etc. See how the book would read less like a novel and more like linked stories if you followed one character, one plot layer, one color at a time.

When I did this activity, I realized that the way I had written fiction for many years was to take it color by color, one plot layer or subplot at a time.

Or to use another analogy: If you handed me the 117 vignettes of Mrs. Bridge out of order, I would have made piles—one for each character, then maybe smaller piles within the large ones. And that would have been my book manuscript. Hey, that’s almost exactly what my first book WAS.

I thought: Maybe a novel could be fashioned from stories by breaking up the piles and laying them out chronologically?

I considered re-typing Mrs. Bridge word for word, or xeroxing the entire book, just to test my theory, to see if these extracted stories would actually read like stories.

Confession: I have done this before with two short stories: “The Things They Carried” by Tim O’Brien, which I xeroxed, cut up and reassembled into “The Jimmy Cross Parts” and the “Alpha Company Parts,” and with Ethan Canin’s “The Year of Getting to Know Us,” which I reassembled into chronological order.

Then I realized that I didn’t have to retype or xerox Mrs. Bridge. The full text of Mrs. Bridge is available online. You don’t want to know how excited I was about this.

6.) Now, extract some short stories from the novel. Go back to your groupings of colored post-its, find the corresponding text online, then cut and paste it into a Word document.

For example: I extracted one short story from the novel called “Etiquette Lessons.” It’s the story of Carolyn’s friendship with Alice Jones, alternated with vignettes of Mrs. Bridge “teaching” her children about manners and “teaching” her children about race and class. The climax of the story is a scene late in the novel when Mrs. Bridge wonders why her daughter uses a racial epithet and mentions her childhood friend Alice Jones who “looks very black” these days.

7.) If you can reverse engineer Mrs. Bridge, envision this novel as stories which were pulled apart, rearranged, and turned into a novel, then maybe it’s possible to forward engineer your own novel narrative from all those short stories sitting on your hard drive.

Stories into a Novel

Backstory: When I was finishing The Circus in Winter, a few agents read the manuscript. One said, “I will take you on if you let me help you turn these linked stories into a novel.” I said I’d think about it. A few days later, another agent got back to me and said, “I think you should write the book you want to write.” That’s the agent I chose, and I’m glad I did, but if I’m being totally honest here, and I am, I was also relieved that I wouldn’t have to figure out how to turn my stories into a novel. I didn’t think it was possible.

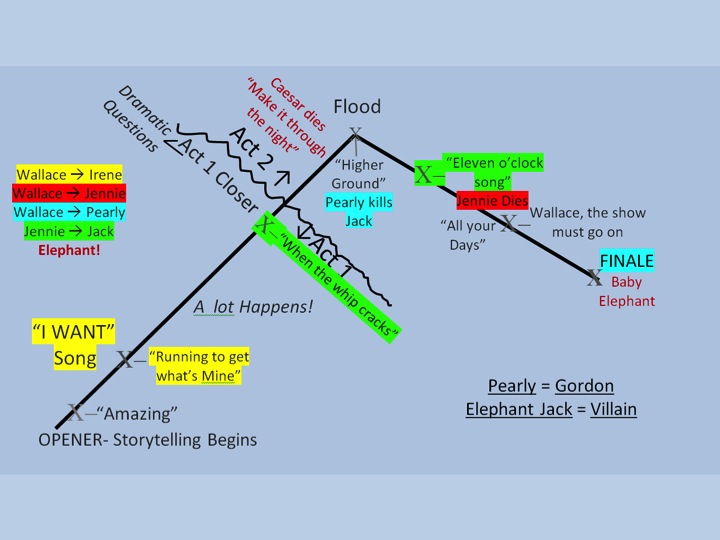

Backstory: Flashforward ten years. A group of college students adapts my book into a musical—and they find a linear storyline in my book. They broke up my piles of stories, laid them out chronologically, and focused on the events of the first five stories. They gave the narrative its “clock,” its basetime (a few months), decided that the flood would be the climax, followed by the denouement. Beginning, middle, end. Badda bing. Badda boom.

If they can do it, so can you.

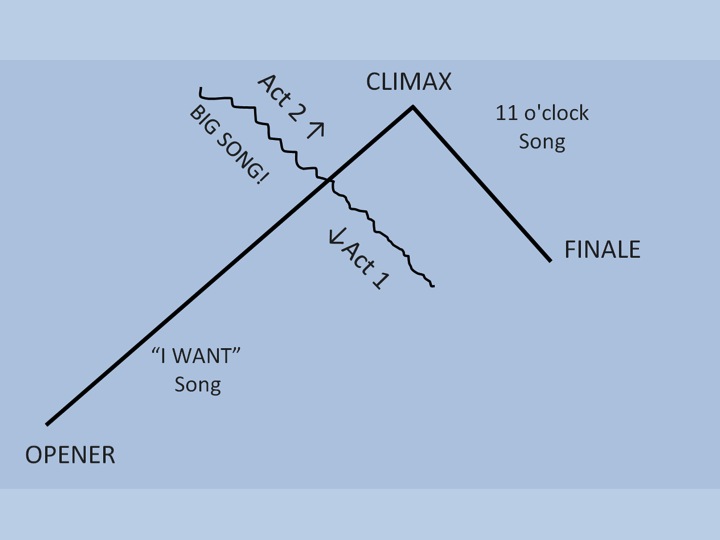

The traditional musical has a familiar structure. There are two acts. Certain kinds of songs happen at certain times. The audience expects this structure, but the artists who make a musical must plug exciting and surprising variables into this structure.

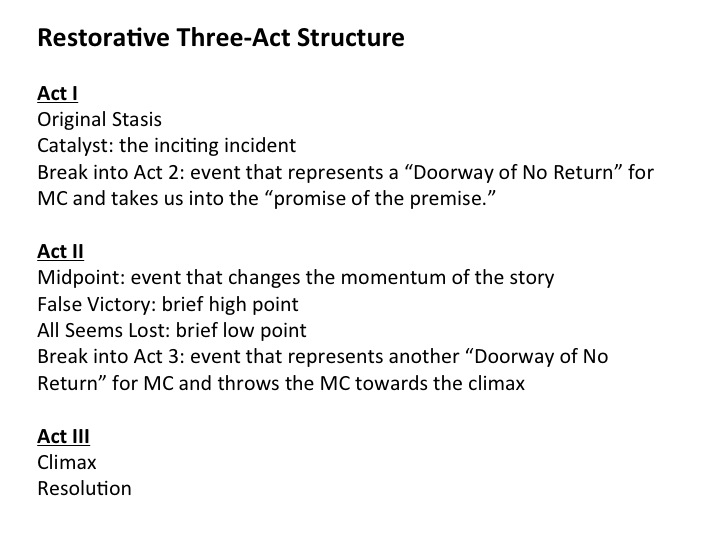

Now, trust me, there is no “formula” for a novel, but generally, we think of it in terms of a Three-Act Structure.

Now: find some linked stories, such as the last three stories in Patricia Henley’s Other Heartbreaks (“Skylark,” “Emma Compartmentalizes in Ireland,” and “Ephemera”).

- List all the events (25-30) that transpire in chronological order.

- Imagine cutting the stories up, moving the pieces around into a more linear or chronological narrative, like Mrs. Bridge.

- Consider a flashforward prologue to begin the novel. Describe the structure of this pretend novel–where it starts, where it ends.

- It might help to decide first what the climax will be–and work backwards and forwards from there. You might be interested in reading this interview with Henley, in which she confirms that “Other Heartbreaks” WAS a novel that she broke apart and turned into linked stories.

- Henley is visiting Ball State on February 15, and my students are eager to hear her talk about writing novels, writing stories, and writing novels that turn into stories.

- Or try this with The Things They Carried. Or with Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad.

Please understand: I’m not saying those books should be anything other than their own wonderful selves.

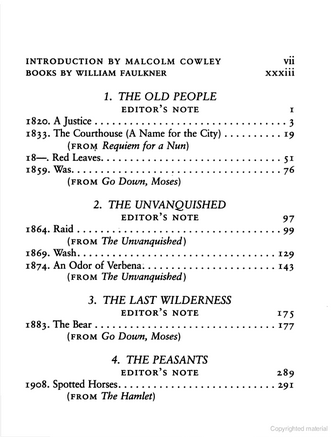

Please understand: Malcolm Cowley did exactly what I’m suggesting when he cut up, chronologically assembled, and edited The Portable Faulkner. And thank God he did. In his now-famous introduction, Cowley writes: “All the cycles or sagas are closely interconnected. It is as if each new book or story was a chord or segment of a total situation always existing in the author’s mind.”

Then: take a few of your own stories that are (or could be) linked. Repeat 1-6 above.

Takeaway

My novel-writing students did these activities. When I asked them, “What did you learn this week,” one woman said, “I have to figure out a way to SEE my novel, to visualize it.”

Another said, “It really matters what you decide to put first, but you probably won’t write the book in the order that it will eventually be read in. I have to stop worrying about my first chapter.”

Exactly.

Teaching Writing

“Write the book you want to write”, good advice, and I’m glad you did. I find myself thinking… “what will people think of this” and changing things. Thank you, Cathy…

Thanks for the great ideas, Cathy. I second Ted’s comment about “write the book you want to write,” but it seems to me that this exercise could help someone find exactly what the book is that they do want to write.

At first blush I’m thinking, why spend all my time doing something like this when I could be spending that time on the writing itself. Yet your words about the “piles” of characters and subplots that would have constituted your early manuscripts quite resonates with me — it shows what these activities can reveal to a writer about the many complex ways of constructing a story.

Many thanks,

–AM

Glad it hit home with you, too. 🙂