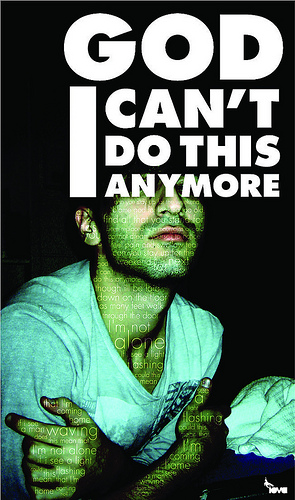

“I can’t do this anymore.”

I’m having a real crisis.

I’m starting to wonder if teaching a novel-writing class with 15 students can really be done.

Let me explain.

This semester, I taught Advanced Fiction, a 400-level course at Ball State which I teach as a novel writing class. The course is capped at 15, and so, because I was assigned two sections, I had 30 students writing novels for me this semester.

Let’s do the math.

- Each student wrote 2,250 words a week (about 9 pages of any quality) for 12 weeks.

Multiply that by 30 students, which means my students produced:

- 67,500 words (270 pages) a week

- 810,000 words (3,240 pages) over 12 weeks

They turned in their Weekly Words via email. I created a special gmail account to receive these messagess so that they would not get lost amid the 50-100 other emails I get every day.

- 30 emails a week over 12 weeks = 360 emails to open, digest, file away.

To make this process easier on me, I asked them to include the following information every single week:

- their logline (a one-sentence description of the plot)

- the context of the words (“finishing chapter 2 this week,” or “This week, I banged out a lot of plot points,” or “random scenes,” or “I journaled some questions and concerns for awhile, then moved into some scenes from what I think will be the prologue.”)

- Then they attached the document that contained their Weekly Words.

I’ve already written about how I “read” these email attachments, which is to say that I look them over but don’t respond.

- Logging in their Weekly Words takes about 2 hours a week.

- Meanwhile, I read and grade other things they write. Their quizzes (I give really long in-class reading quizzes), their reverse storyboard projects (where they take a book apart and write about what they learned), short response papers, etc.

This will not surprise you: it’s really hard (but not impossible) to absorb this many stories coming at you at once. But within a few weeks, I do get to a point where I remember what each of them is writing about.

For twelve weeks, they send me the fragile stirrings of their novels. It’s weird feeling to receive those 30 emails every week, something strangely intimate and kind of a privilege. I treat their words very carefully. I acknowledge the receipt of their Weekly Words by sending a brief reply. I don’t say much other than “Thank you,” or “Keep going!” or maybe “I liked the scene at the party.”

It’s way too early to say anything critical.

And pedagogically speaking, it is relatively easy to read through words and pages I don’t need to respond to critically. Yet.

The Consequences

The Consequences

Still, it’s a lot of words coming at me. Even if I’m not commenting, I’m still making room in my head for all those words and stories. There are definitely consequences.

- I watched a lot of TV and movies this semester.

- When friends and former students asked me to read drafts of their novels and memoirs (this happened about once or twice a month), I had to say “No. I don’t have any more room in my head.”

- I worked on my own book project until about Week 8, and then I had to stop. This happens most semesters, though, even when I’m not teaching novel writing.

- Eventually, I *do* have to read and respond to them all. (More on this later.)

Comparison

Now, if this were a different class, a “normal” fiction workshop, I wouldn’t be quickly reading 270 pages a week. I’d be carefully reading maybe 50-150 pages of fiction due to be “up” in my workshop that week.

And so would all 30 of my students.

See, the students in my classes aren’t looking at 270 pages a week. Only me. There is no all-group workshop in my class. They’re expected to spend a lot more time writing their own stuff than they spend reading the work of their peers.

In fact, for many weeks, they really have no idea what anyone else is even writing about.

The Climax of the Semester, or Shit Gets Real

Then, in week 14, they have to turn in a partial, which I define as the first 25-50 pages of the book.

By this point, I’ve put them in small groups—the ones writing realism, the ones writing fantasy, etc.—and they read only those partials. I don’t even call these discussions “workhop.” I call it “beta reading.”

But—and you saw this coming, right?—I have to read them all. This is when things get really, really hard.

25-50 pages times 30 students = 750-1500 pages.

This is how I do it

This is how I do it

- I’ve been an MFA thesis advisor. This is nothing at all like that. No way. Thesis advising involves reading at both the micro and macro levels. This is macro only.

- To keep myself from doing line edits, I send the documents to my Kindle. This keeps me from marking all over them. I try to “just read.” I make a few notes to myself.

- I don’t type a critique. Each student makes a 30-minute appointment, so I give my feedback orally. They walk out with a rubric where I’ve marked the things they need to work on for the revision (due at the time of the final).

- I spread these appointments out over 2 and 1/2 weeks, doing about four a day. Which means I read just four a day. That’s all I can hold in my head.

So Tuesday, for example, I had four appointments scheduled, plus a meeting and a class to teach. I read one partial Monday night before I went to bed, then got up about 6:30 to read the other three. Got dressed. Went to school. Taught. Conferenced. Came home. Had dinner.

As I write this now, I have five appointments scheduled for Wednesday which means five partials or about 200+ pages to read, and I’ve only read one of them. And my morning reading time is gone because I’m teaching from 9-12 in the morning.

So every word I’m writing here is cutting into the time it’s going to take me to read those 200 pages.

But I needed to do the math.

Conclusions:

- There’s a good reason why very few people teach novel-writing classes comprised of 15-20 students. BECAUSE IT’S REALLY REALLY HARD.

- Even spread out over 2 and 1/2 weeks, I couldn’t handle that many pages coming at me and that many conferences in an otherwise already full life. My physical therapist and my yoga teacher/masseuse and my husband tell me all the time, “If you don’t have time to take care of yourself, something’s wrong.”

- The traditional workshop structure guarantees that you read works-in-progress at a reasonable rate, one at a time, a few a week. Not 30 at a time in dribs and drabs for 12 weeks and then boom, 30 manuscripts fall in your lap (or into your Kindle).

- There must be a way to make this work. I think I’ve ALMOST got it figured out.

- I can’t ever teach two sections of this class again. Luckily next semester, I have just one section.

- Rather than schedule individual conferences, I’ll be a part of the beta reading groups.

- But how can I do that when they’re all discussing at the same time in small groups? Aha. I’ll put them in groups 3 groups of five. The week I spend discussing the mss. of Group 1, Groups 2 and 3 will get in-class writing “studio” time (which they already do anyway). So: I only have to read five partials a week for three weeks, and I don’t have to schedule conferences because they will have gotten my feedback in class.

- I’m also considering reducing the partial to 10-25 pages, which is actually more in line with the industry standard anyway.

More Math.

These are the numbers that count.

Most Words Drafted Contest (top 7)

ENG 407-2

- Kayla Weiss 85,007

- Scott Bugher 65,878

- Andy House 62, 353

- Sarah Hollowell 52, 025

- Amy Dobbs 38, 365

- Jackson Eflin 32, 971

- Samantha Zarhn 27, 393

Each of these students wrote more than the required 2,250 words a week.

I’m convinced that the real test of teaching is figuring out a way to make your students feel like they’re working and learning WHILE ALSO making sure you yourself are staying productive as a writer. Because how can I expect them to write if I’m not? I think I’ve almost got this class to a point where we’re all writing and nobody’s buried.

I’ll report back next semester and let you know.

Teaching

I’m so glad you’ve come to the conclusion that you can make this class work because it’s SO valuable. As I’m writing my book proposal (!) and preparing to send my revised first 30 pages out, I can’t help but think back to how much I learned in this course and how much it has helped me take my creative endeavor and professionalize it.

Without the guidance I received in your class, I would be utterly lost right now.

You do need to take care of you first, but if you can do both, I sure hope you try!

Ashley you took the class when it was still a write shop. I do it a little different now. I’m glad you’re still working on your book.

I’m so glad you’ve come to the conclusion that you can make this class work because it’s SO valuable. As I’m writing my book proposal (!) and preparing to send my revised first 30 pages out, I can’t help but think back to how much I learned in this course and how much it has helped me take my creative endeavor and professionalize it.

Without the guidance I received in your class, I would be utterly lost right now.

You do need to take care of you first, but if you can do both, I sure hope you try!

Cathy,

I’ve just about finished another UCLA Extension class, Write a Novel in a Month as Part of NaNoWriMo. This term I had 30 students and 27 of them completed the 50,000 word draft during November. Other instructors ask me how do I manage to read all that material. As I’ve said many times before, I don’t. It’s a “writeshop” not a workshop. Extension offers a couple of hundred workshops so there’s no need for another. This one is pure writing. At the last class, these newly minted (first-draft) novelists are invited to read a selection of their work (in progress) to the class. I make my parenthetical qualifications because it’s a more accurate representation of the situation. At the reading, this will be the first an only time I hear the work. No workshopping, no comments. Just a reading.

A couple of years ago we ran a revision of your first novel class to immediately follow the one I’ve described. I had 12 students and we read a 120 page selection of each person’s novel (in two rounds of 60 pages each). Full workshopping was expected and I have to say the experience was difficult. My wife says the same thing. The time sink was unbelievable. Look, there’s always something else you can point to in a piece. I finally realized that if I came up with two or three suggestions for revision to the next draft, that was going to be sufficient. Anything more than that was too much information for the writer to process. The first round, I hadn’t figured this out yet so while the critique was perhaps more comprehensive it wasn’t as useful. The second round backed off and I think it allowed the writers to at least have an approach to the next draft.

So maybe that’s the answer. Take the approach to drafts from Robert Boswell who advises considering a single issue. What’s the single biggest thing going on in the piece that needs looking at? Don’t solve for everything, solve for the next draft.

Ian that is gooooood advice.

Your over-the-top commitment to the development of aspiring writers is admirable and plays a big part in making my non-traditional undergrad experience something to treasure. Entering your class, I had a stubborn and sour attitude towards just about everything: planning, storyboarding, prep-work, genre fiction, etc. Now index cards and prepped scenes excite me and I respect a broader scope of literature. You’ve really chipped away several layers of my closed mind and I really appreciate that. I hope you’ll find abundant rest after you’re through with final revisions and that you’ll have more room to breathe next semester.

Thank you!

Your over-the-top commitment to the development of aspiring writers is admirable and plays a big part in making my non-traditional undergrad experience something to treasure. Entering your class, I had a stubborn and sour attitude towards just about everything: planning, storyboarding, prep-work, genre fiction, etc. Now index cards and prepped scenes excite me and I respect a broader scope of literature. You’ve really chipped away several layers of my closed mind and I really appreciate that. I hope you’ll find abundant rest after you’re through with final revisions and that you’ll have more room to breathe next semester.

Thank you!

You are a teaching novel writing GODDESS for almost (your words) figuring this out!

Whew! I was beginning to feel like the Lone Ranger with the reading and workshopping if student work I do. But you have taken it to a new dimension, kemo sabe.

Seriously, this does show why it’s so hard for writers who teach to get their own work done, past a certain point, if they are doing a good job of teaching writing. So much reading, so much grading. I have colleagues who have worked for years, nay: decades, on books, and the better and more conscientious they are about teaching the longer it takes them. I’m impressed you managed to chip away at your own work for eight weeks, and that is worth a post too. Because at least it’s something. Everyone I know tries, but at some point in the semester at teaching institutions their efforts tend to collapse.

OTOH, how lucky are your students, Cathy. And it’s quite an accomplishment to be teaching narrative writing at your level. You obviously manage to demystify and work for them to an awesome degree.

Whew! I was beginning to feel like the Lone Ranger with the reading and workshopping if student work I do. But you have taken it to a new dimension, kemo sabe.

Seriously, this does show why it’s so hard for writers who teach to get their own work done, past a certain point, if they are doing a good job of teaching writing. So much reading, so much grading. I have colleagues who have worked for years, nay: decades, on books, and the better and more conscientious they are about teaching the longer it takes them. I’m impressed you managed to chip away at your own work for eight weeks, and that is worth a post too. Because at least it’s something. Everyone I know tries, but at some point in the semester at teaching institutions their efforts tend to collapse.

OTOH, how lucky are your students, Cathy. And it’s quite an accomplishment to be teaching narrative writing at your level. You obviously manage to demystify and work for them to an awesome degree.

Cathy,

I can’t imagine teaching novel writing to 30 students in one semester. Wow! Please don’t do that again. For what it’s worth, when I teach the course, which is only every two to three years, I don’t read the stories when I do a work count. They bring their laptops to class, or a jump drive; they open up their file; I check their total word count and note in my grade book if they met the word count expectation. Then I’m done. I do put myself in a peer review group–3 people in each–and thus I read a couple other student’s novels as they progress over the course of the semester. And I write critiques for these students. But as for the rest of the class, I don’t see their novels until the very end. Now, while that makes less crazy reading over the course of the semester, I am dumped on quite a bit at the end. Last time I did this, I was still reading the novels over Christmas break. That sounds nuts, I guess, but on the other hand I was able to write my own short novel that semester while the students did theirs.

Hey, Cathy,

I’m reading almost as fast as you do your novel entries, and getting ready for a traditional (mostly short story-based, but not entirely) workshop this afternoon. Question: Have you done this with graduate students, and maybe a smaller class. In our small program, it’s not unusual to have 8-10 people in the class, and many of them want to write novels but only a few will subject their novel-in-progress or would-be-novel to a traditional workshop’s critical scrutiny (in fact, I warn them of potential negative consequences of that.) I’d like to talk to you about that, sometime. Is Michael, in his Hypoxic workshop, working with undergrads, grads, or both? Hope all’s well with you, all that speed-reading aside.

Brad

Hi Brad! I’m happy to talk more. I know that Matt Bell at Northern Michigan has been doing this with grad students. I only do this with undergrads actually.