You Are Here: Teaching Students about Middletown, Indiana

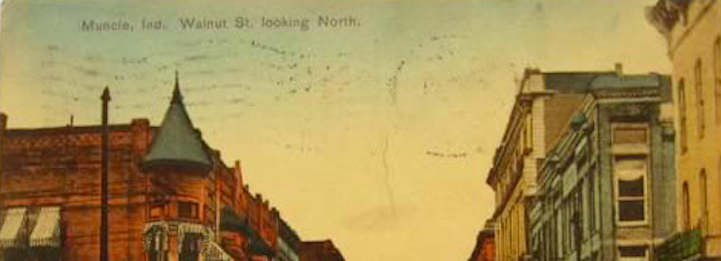

This semester, I told my students that once upon a time, Muncie, Indiana was a boom town.

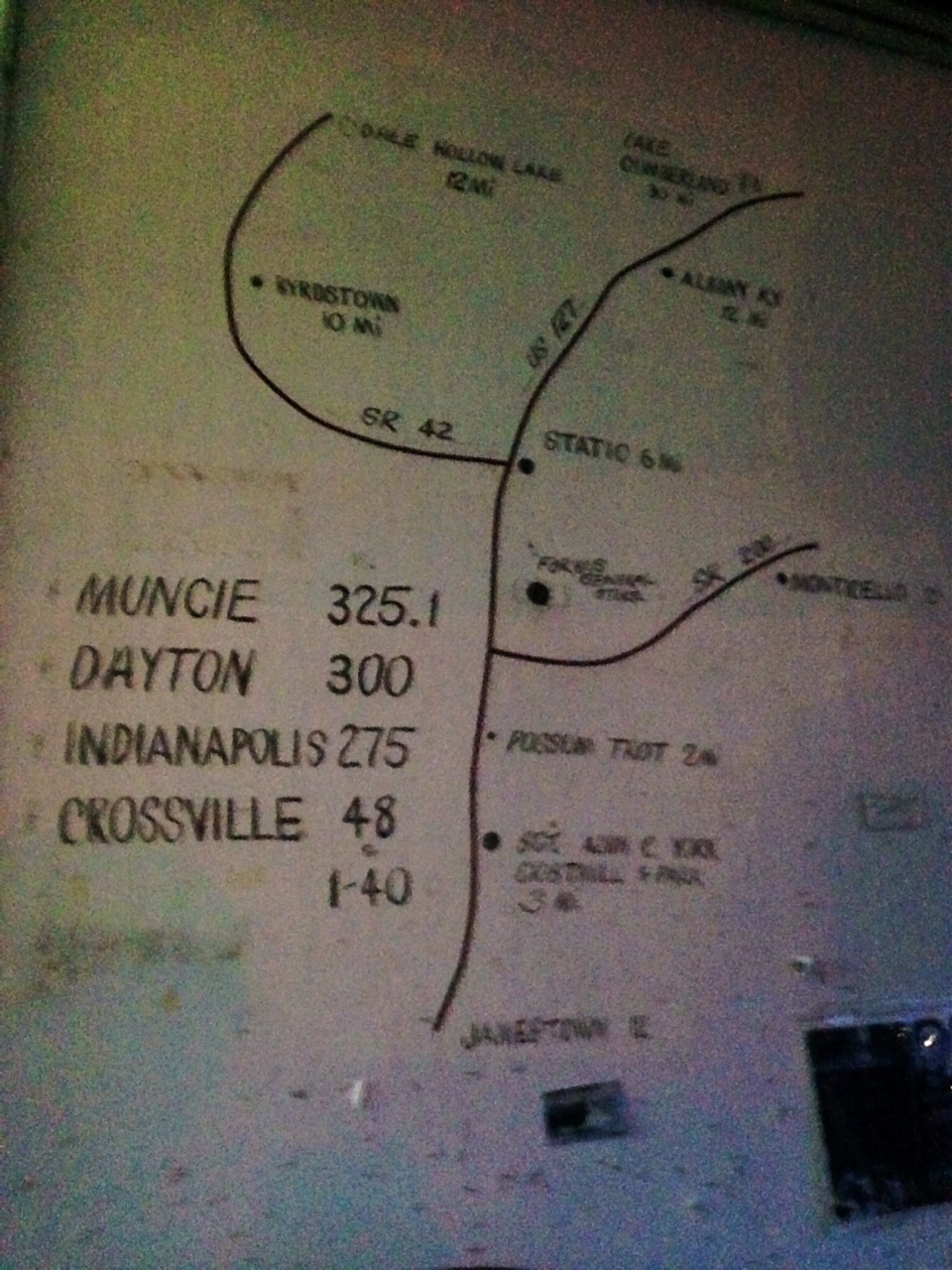

To prove it, I showed them this picture, taken by my Ball State colleague, Lee Florea. He hails from a small town in Kentucky, and this map is still painted on the wall of the local general store.

If this picture had a title, it would be, “Here’s Where the Jobs are How to Find Them.”

Once upon a time, a “river of immigrants” from Appalachia thought of Muncie as the Promised Land. The jobs they came for are all gone now, and Muncie is in the process of re-inventing itself. (Please, for the love of god, let’s hope it does, because I bought a house here, folks.)

My students are in college. They come to school from Indianapolis or Fort Wayne or Terre Haute and drive to their dorm, maybe to Wal-mart, maybe to Chili’s. Campus is their “home,” not Muncie itself.

How do you make a new place your home–even if just for a little while? That is a question I’ve been trying to answer for a long time.

For me, the answer has always been: learn the history. Immerse yourself in it. Travel through time.

I wanted to share that experience with my students.

Another New Class

So, during Spring 2015, I taught a new course: ENG 444, the senior seminar in my department. I called it “Research and Fiction.”

Actually, I’ve wanted to teach this course since I arrived at Ball State in 2010. It’s the capstone course in English and comprised of students from all concentrations (Creative Writing, Literature, English Studies, Rhetoric and Writing, and English Education). Their capstone project in our department must be a “major, student-driven research project.”

Did you know that The Circus in Winter was my undergraduate capstone project? It was a major, student-driven research project, too.

Not a research paper, but rather a researched story.

By teaching ENG 444, I wanted to demonstrate that “a researched story” and “a research paper” aren’t that different.

Actually, I wanted to demonstrate that the creative process and the scientific process aren’t that different.

I mean…look! –>

In my class, we discussed these essential questions:

- What does “research” mean in the making of art? How do writers conduct research and incorporate it into their work?

- When should you do research? At what part of the writing process? How do we avoid over-researching? How do we determine what material is relevant to our fiction and what’s not?

- What forms can this research take? (reading books, interviewing experts, engaging in immersion journalism/ethnography, taking research trips to libraries or archives, and, of course, Googling).

- What are the rewards and dangers of purposefully doing research as a fiction writer?

As someone who writes researched fiction, all of these questions are of great interest to me.

Here is the result: 16 linked stories set in historical Muncie, Indiana available for your reading and downloading pleasure on ISSUU.

And it’s also been added to the Ball State Middletown archives, which is very cool.

As you read the stories, you’ll see that:

- The stories are linked by setting, character, and major events.

- This anthology pays homage to the long history of Middletown Studies.

- “Middletown” is a whole lot like Muncie, Indiana.

- Every student in the class—not just the creative writing majors—contributed to the anthology.

Linked Stories

In The Triggering Town, the poet Richard Hugo advised his writing students to distance themselves from their real hometowns by creating a fictionalized place to call their own, a “triggering town.” This practice has a long-standing tradition in American literature:

- Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River

- Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg

- Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County

- Sinclair Lewis’ Gopher Prairie

These works inspired my own book The Circus in Winter about “Lima,” Indiana, a not-so-clever pseudonym for Peru, Indiana.

We began the semester by reading:

- Winesburg, Ohio by Sherwood Anderson

- The Sweet Hereafter by Russell Banks

- A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan

We talked a lot about the form, the difference that story order makes, and the ways in which the authors had purposefully linked their stories.

Using these books as models, my students began to create a fictional town. We called it Middletown, Indiana.

Middletown

As you may know, Muncie is one of the most thoroughly studied cities in the country; in 1929 and again in 1935, sociologists Robert and Helen Lynd came to town in search of a “typical” American city, which they called “Middletown.”

Ever since, whenever researchers or journalists want to take the temperature of America, they come to Muncie—because it’s considered the most average small city in the country (which made my students chortle), a community that’s seen as the barometer of social trends in the United States.

We acquainted ourselves with the Middletown study by:

- reading portions of the book, Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture

- watching portions of the Middletown documentaries (the landmark series from the 1980s)

- touring the Middletown archives, thanks to Digital Archivist Brandon Pieckzo.

- I also showed them this work of video art by my Ball State colleague (and neighbor) Maura Jasper, “Wish You Were Here.” She begins with a historical photograph and then slowly fades in a video of that site in the here and now.

Then they started writing. The only rule was that they had to set their story in a year in which they were not alive.

We also decided for sure that our Middletown would not be as white or as straight as the Lynd’s.

Structure

The Middletown study was famously divided into six “spheres.”

- getting a living

- making a home

- training the young

- using leisure

- engaging in religious practices

- engaging in community activities

Initially, I wanted to organize our anthology in the same way, but I decided it might be best to let students write whatever story interested them the most, in whatever time period interested them the most, in whatever sphere interested them the most.

What emerged were stories that were set from the 1920’s to the 1980’s. They dealt with race and class and gender, politics, war on the home front, unsolved mysteries, and friendship.

At first, there wasn’t much linking the stories except for the fact that they all took place in Middletown.

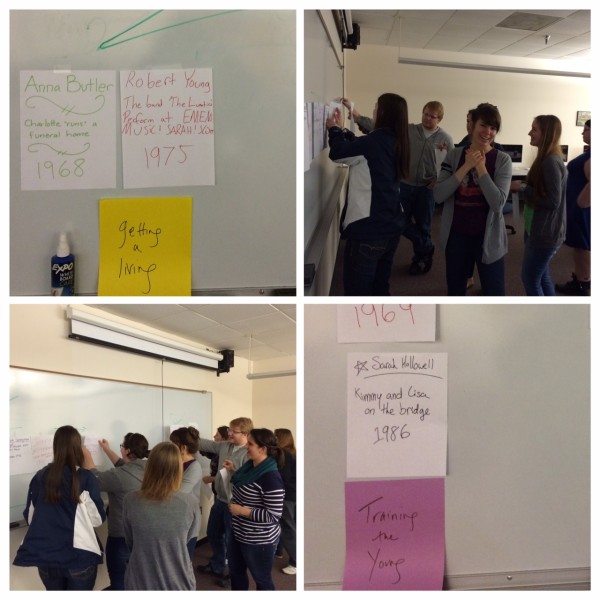

Then, I grouped the students into four groups of four.

- The 1930’s group, which was about Muncie’s (and Indiana’s) troubled racial past.

- The 1940’s group, which was about WWII.

- The 1960’s group, which was about cultural changes.

- The 1980’s group, which was about characters trying to leave Middletown.

They read each other’s stories and created “nodes of conjunction” between their stories. The main character in student A’s story became a secondary character in student B’s story. The setting of Student C’s story was incorporated into Student D’s story. And so on. You’ll recognize those linkages as you read.

Instead of an all-class workshop (which would have taken a full month of the course), they each gave a presentation: sharing a bit of their research and inspiration, followed by a short reading from their story.

Students voted on the title, the epigraphs, the order.

We did a storyboard of the anthology, laying all of the stories out on the board. We discussed how to best begin and end the book, whether to use chronological order or thematic order.

Ultimately, we decided on a roughly chronological order, but we did pay homage to the six thematic spheres—albeit in an ironic way. (Check out the anthology and see!)

It’s worth mentioning that students were not graded on their short stories, but rather on the essay they wrote about the writing and research process that produced the story.

What They Learned

Emphasis mine.

I found that even one sentence, or the premise of a story, takes research. I knew that the majority of things “historical” would have to be looked up, but I didn’t realize that every single part of the story is dictated by the time period. I also learned how to do research for characters; through other books and personal experience. This process was very important because growing up in academia, we are told to always look for “valid, credible sources” such as academic journals. However, those sources would not have been as helpful as photos of clothing or the map of Ball State’s campus in 1968. This process has changed my opinions on what is research and what its overall purpose is in writing and life.

In a literary analysis paper, which is what I’m much more accustomed to writing, you shine a light on your research. In researched fiction, though, the research needs to be invisible. This has consistently been one of the hardest parts of doing this research and writing this story. I do all this research and I want to say, “Hey! Look! I did all this research!” But this is not a research paper. Remembering that everything I put into the story has to be there for a reason, has to contribute and move the story forward in some way, was the most important thing that I had to constantly keep in mind throughout this process.

The research process, as I conducted it this semester, became much more of an unstructured process of exploration than the strict, orderly thing that I’ve always thought research to be. This de-familiarization of the research process has been an encouraging experience, teaching me that doing research is nothing to be afraid of, and furthermore, that it can be fun. I am happy with this outcome, because research is something that we, as human beings, do every day and in every situation, every time we survey a room, every time we pull out a smart phone, every time we ask a question of another person. It would be a shame to fear these things, to fear knowledge.

At some point in my school career, I became a lazy researcher. For term papers in elementary school I would go to the library and pour through book after book, making careful notes all along the way. In high school, I became a Googler. If I couldn’t find the answer in a Google search, I tended to decide that I didn’t really want or need to know it. I unlearned some of this in college, but I was still first and foremost a Google addict. I knew there were other sources out there, but I didn’t understand their value – and I didn’t until I started looking at research from a creative writing perspective. If you wish to truly understand and represent something in your fiction, it is not enough to Google the answers. Research must combine common sources like Google and books with out of the box sources like taking field trips and finding old yearbooks and popular magazines.

Throughout my journey to the final product, my research took many forms. I conducted interviews, analyzed photographs, watched videos, read magazines, watched documentaries, went to a house where a murder took place, read news articles, and looked at maps. Did everything appear in my story? No, but each source was rewarding in its own way because research, no matter how insignificant it seems, is still significant.

The End

I’m so glad that my students learned these things. I’m incredibly proud of the work they put into these short stories. And I’m humbled that we are adding another research artifact to the Middletown Studies archives.

And so I give you You Are Here: Finding Yourself in Middletown.

P.S.

I’m sorry that I didn’t blog while I was teaching this class. I wanted to, but just figuring out how to teach it sort of overwhelmed me!

P.P.S.

To my students, I’m sorry that I had to figure out how to teach this class as I went along. I appreciated your patience.

Teaching

What a wonderful project. Concerning research, I’ve always learned to write from the overflow. Research enough that you are steeped in it and then write from the position of more than enough knowledge.

There is always room for spot checking and more details but as someone who can get lost in endless research, I have a hard time deciding I know enough to start.

Oh yes. We talked a lot about how much research is TOO MUCH, especially when you can Google!