Research isn’t something I do to flesh out my ideas. Research is how I get my ideas.

Writer Mario Vargas Llosa has said that he requires “the springboard of reality” to ignite his imagination, and I would say the same. Here’s a story about why I love doing research and why I write what I’ll call “nonfictional fiction.”

So, in March of 1902, my main character’s brother-in-law tried to divorce his wife. Theirs was a tawdry story, and it made all the papers for about two years.

Since the trial happened in Chicago, I wanted to see how the trial was covered there vs. how it was covered in the New York press. This involved going to the library here at Ball State and scrolling through the microfiche.

Bingo. I found what I was looking for. Drawings of the principal characters. Testimony read into evidence.

Now, I don’t know if my character actually went to this trial or not, but it’s certainly more dramatic if she was there. So I made it happen. Presto.

So, the other day, I was writing those scenes. Linda in Chicago at this divorce trial. March of 1902.

I decided to have her stay at the famed Palmer House. Why? Well, I stayed at the Palmer House for AWP 2012, and so this way, I can write off some of my expenses.

Also, it’s gorgeous.

While I was staying there, I grabbed a flyer about the history of the Palmer House and gleaned two great details:

- The floor of the barber shop was tiled in silver dollars.

- The owner was so sure that his hotel was “The World’s Only Fire-Proof Hotel,” he promised that if any of his guests were willing to pay to remodel and replace their room’s furnishings, they could set their hotel suite on fire and close the door. Potter Palmer vowed the fire wouldn’t spread, and he was willing to prove it. (His original hotel burned down 13 days after it opened in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, and Palmer rebuilt his hotel out of iron and brick.)

When I saw those details, I knew my character’s rich, bad-boy husband wouldn’t be able to resist setting his hotel room on fire, and that he’d want to show her that floor tiled in silver dollars.

So, I knew from the Chicago Tribune coverage that the divorce proceedings ended suddenly in a mistrial. My character had a whole day before her, plus I needed to give her husband time to set their hotel room on fire. What would she do with the day?

I decided to send her to a museum, the famed Art Institute of Chicago. Was it open in 1902? A quick Google search told me yes, it was.

Well, what would she have seen?

We all know from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off that the museum is famed for its Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings, (like Seurat’s “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jette”) but in 1902, they hadn’t acquired much of that yet. So I Googled:

what would have been on exhibit at the art institute of chicago in 1902?

And I found this: a list of all the exhibits for that year with links to the digitized exhibit catalogs.

Three cheers for archivists! Three cheers for the digital humanities!

Can I get an amen?

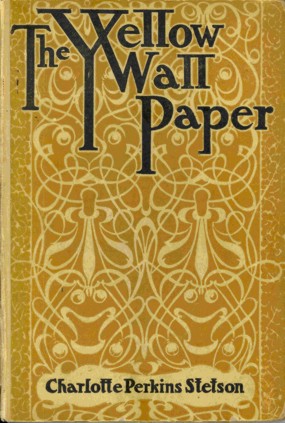

Randomly, I clicked on the name “Charles Walter Stetson,” then Googled his name, and discovered that Stetson was married to Charlotte Perkins Gilman. In fact, when she first published “The Yellow Wall-paper” in The New England Magazine in 1892, she was still Charlotte Perkins Stetson.

I also discovered that Stetson painted a portrait of Gilman shortly after the birth of their daughter, a time when she was likely experiencing the post-partum depression that she chronicled so vividly in the story.

So I came up with a plot device that would allow Linda to see this painting (although it actually wasn’t in the exhibit) and become intrigued enough to read her recently published book, The Yellow Wallpaper.

There’s a library in the Art Institute. Was this book there in 1902? I don’t know, but I’m hoping the reader will permit me a little creative license.

So I sat my character down in the Ryerson Reading Room and had her read “The Yellow Wallpaper,” and she has a kind of epiphany that day.

She’d been needing an epiphany for awhile. I just had no idea what might trigger it. No idea that a simple Google search would end up determining a major plot turn in my novel.

Then she returns to the Palmer House to discover that her husband has burned their suite.

Sometimes, I think young writers feel that “creativity” means “making up out of whole cloth,” but I’ve never felt that way.

Serendipity means a “happy accident” or “pleasant surprise.” Specifically, the accident of finding something good or useful while not specifically searching for it. For me, serendipity is part of the euphoria I feel when I’m inside the creative process. I like it when my character’s “real” life (whether it’s my life or someone else’s) provides some plot points to shoot for.

But too much plotting can be…well, plodding. I find that when I’m writing and/or researching, I have to keep my plan, my goals rather loose to allow for serendipity, magic, and imagination.

I like following bread crumbs, like the trail I just described to you. It’s like playing detective.

That afternoon, I read “The Yellow Wall-Paper” not as myself but as my character. I found something out about her that I hadn’t known before. Or hadn’t been able to articulate before.

And who is to say that this wasn’t exactly the way that discovery was “supposed” to happen?