These questions have been on my mind for quite a while:

Why did I spend twenty years working on short stories as opposed to novels? Is it nature or nurture? Am I really predisposed to write short stories, or do I write them because it is the only prose form for which I received explicit instruction?

How do you write a novel? And how do you teach a class on how to write a novel?

Is our current and much discussed market glut of short stories due to a genuine commitment to the form, or is it due to the fact that the many, many writers we train in creative writing programs simply don’t know how to write anything else?

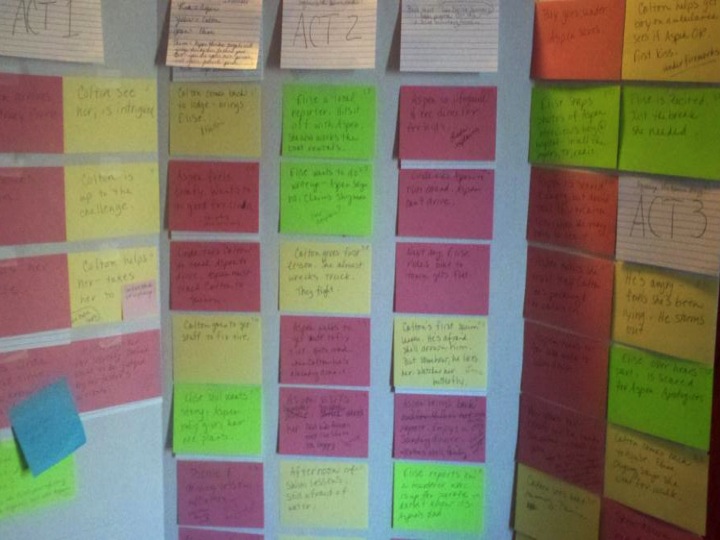

Is a workshop antithetical to generating a big thing? Is it possible to teach a class that is a “writeshop,” not a workshop? What would that look like?

Gradually, I’ve incorporated all this thinking into my classes. And also–because for me teaching and writing are inextricably linked–I’ve incorporated all this thinking into my own writing practice; I’m in the beginning stages of a novel. Not a novel-in-stories this time. A novel. I created this blog in order to share this journey with others trying to make the same shift from “story” to “book.”

There are an infinite number of venues to talk about creative writing, but not as many to talk about teaching creative writing–which is unfortunate, because I absolutely love to talk about teaching creative writing. That’s one of the reasons I love being friends with writer/teachers on Facebook; we share what we’re doing, how we’re doing it, what’s not working, what is working.

I’ve never blogged before, but I’ve wanted to for a long time. The best way to begin, they say, is to begin with what you’re passionate about, and right now, this is what I’m passionate about: the big thing–generating one, revising one, publishing one, teaching others who are interested how to do it, too.

This blog isn’t very slick, and I know I have a lot to learn. I came very close to not starting the blog for those reasons. I’m a Virgo, a perfectionist. My impulse is to spend hours fiddling with the format, figuring out everything about how this works–but I can’t. I have a big thing to write. And students who have a big thing to write.

Onward.

vignettes (in this order: 61, 39, 37, 60, 91, 99, 84, 86, 18, 102, 41, plus one titled “Equality” not found in the novel).

vignettes (in this order: 61, 39, 37, 60, 91, 99, 84, 86, 18, 102, 41, plus one titled “Equality” not found in the novel).